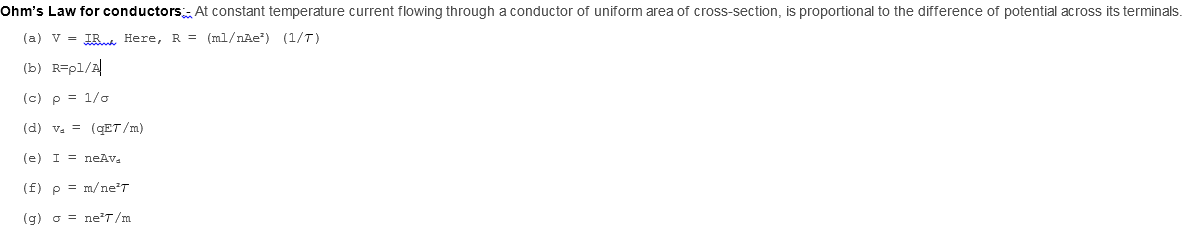

Ohmís Law

Ohmís

law states that the current (I)

flowing through a conductor is directly proportional to the potential

difference (V) across the ends of the

conductor.

![]() †

†

We know that, ††††† ![]()

but,

†††††††††††††††††††††††††† ![]()

therefore, †††††††††††††† ![]()

also,

††††††††††††††††††††††††† ![]()

therefore,

![]() †or

†or ![]() †= R a

constant for a given conductor for a given value of n, l and at a given

temperature. It is known as the electrical resistance of the conductor.

†= R a

constant for a given conductor for a given value of n, l and at a given

temperature. It is known as the electrical resistance of the conductor.

Thus, V = RI this is Ohmís law.

Ohmís law is not a universal

law, the substances, which obey ohmís law are known as ohmic

substance.

Limitations of Ohm's Law

Although

Ohmís law has been found valid over a large class of materials, there do exist

materials and devices used in electric circuits where the proportionality of V and

I does not hold. The deviations broadly are one or more of the following

types:

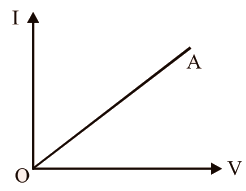

(a) V ceases to be proportional to I (below fig).

The

dashed line represents the linear Ohmís law. The solid line is the voltage V versus current I for a good conductor

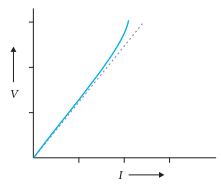

(b) The

relation between V and I depends on the sign of V. In other words, if I is the current

for a certain V, then reversing the direction of V keeping its magnitude fixed,

does not produce a current of the same magnitude as I in the opposite direction (below fig). This happens, for example,

in a diode.

Characteristic

curve of a diode.

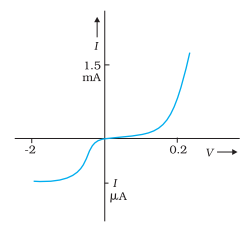

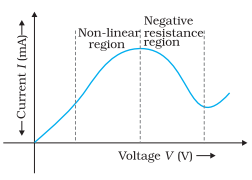

(c) The

relation between V and I is not unique, i.e., there is more

than one value of V for the same

current I (below fig). A material

exhibiting such behaviour is GaAs.

Variation

of current versus voltage for GaAs

Materials

and devices not obeying Ohmís law in the form of V = RI are actually

widely used in electronic circuits.